Fake news and hoaxes: are you looking for information or just confirmation?

In the wake of events such as Brexit, Trump’s election and the rumours about Russian hackers interfering with political events in USA and Europe, post-truth has been chosen by Oxford Dictionaries as the Word of the Year 2016. The awareness of the danger represented by the spread of fake news over the web has risen to unprecedented levels and this, in turns, ignited an already intense debate over the earthquake that is running through the information system, where the official narratives always seem to be weaker than the alternative ones. The mediation layer represented by journalists and experts does not exist anymore.

Such a disintermediation is not limited to politics and economics but involves all complex and articulated topics – including science and science journalism – in relation to which false information and different interpretations, both instrumental or not, are often born. Issues related to emerging infectious diseases (i.e. stigma against migrants during Ebola outbreak) and vaccines (i.e. misinformation about false links between them and autism) are in the spotlight. Many people now point the finger at social media, holding them responsible for the wide, pervasive and unstoppable spread of fake news and hate campaigns. The debate is still in its infancy and tends to put all these elements in a single pot, that of a post-factual society.

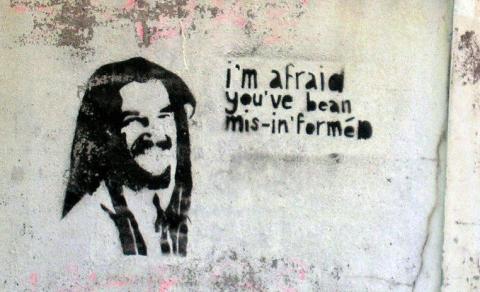

Internet – and social media in particular – destroyed the mediation mechanism within the information system in favour of a more crowd driven process of agenda setting. Indeed, an impressive amount of tailored news and interpretations circulates on the web and feed prior convictions. People find the information that suits them, guided by their prejudices and by confirmation bias. Everybody does that, without exception.

The information is not processed as true, but as a confirmation of a personal view of the world. The very broad range of sources, versions and contents on the Internet maximizes this process. We performed a Quantitative analysis on social media (made of millions of users), showing that we tend to choose a story without really caring about its validity; the most important thing is that we like it. The post-truth is just another way to say that information consumption is driven by confirmation bias.

We tend to acquire information not because of its intrinsic value and credibility, but rather because it confirms our thesis, our beliefs, our prejudice. If we are sceptic towards vaccines, we will like and share news about their low efficacy or mentioning a side effect, while ignoring favorable contents. The more an issue becomes complex, the more our cognitive limits and our tendency to approximation – where confirmation bias is even more powerful – are revealed. The intellectual world, like the information one, is a cauldron of opinions, positions and voices. A world of tribes: pro-vaccines versus anti-vax, with no distinctions and shades. And the main behaviour that stands out is the annihilation of the opponent (kind of identification bias). Probably the best way to fight fake news is to start thinking about what leads to such a polarization, since this seems to be the real enemy. Polarization dramatically characterises the way information is processed and commented, giving rise to symmetries of an almost mathematical regularity. A game of contrasts and opposing arguments.

In light of these results, the idea of introducing fact checking – or even worse, fact checking-based search engine – as a countermeasure is childishly naive, as well as a source of further polarization and acrimony. There is a space to reshape, a trust to rebuild. Speaking without knowledge of facts, just to defend our own positions, should be avoided. There is too much chatter, too much speculation. We should learn to accept the uncertainty that invariably follows complexity. As Cass Sunstein says, we have to promote the culture of humility at the expense of sterile and egoic rhetoric.

Walter Quattrociocchi

Head of the Laboratory of Computational Social Science at IMT Lucca in Italy